1. Complex geological settings and hydrogeology

The complex geology of Serbia and adjacent areas has produced hydrogeological heterogeneity and considerable variety in aquifer systems and groundwater distribution. Paleozoic formations, magmatic and metamorphic rocks, Jurassic and Cretaceous flysch or deeper and thick sedimentary complexes mostly represent aquitards or aquicludes. In contrast, the Mesozoic carbonate rocks, and Tertiary or Quaternary alluvial and terrace deposits can be very rich in groundwater and ensure water supply to most of Serbian population. Neogene and Pleistocene sediments tapped by many boreholes are the main sources of water supply for numerous small and medium size cities in the northern part of the country within the Pannonian Basin, as well as several smaller inter- mountainous basins in the central and southern parts.

The territory of Serbia features a diverse lithologic composition and structure. Several hydrogeological provinces can be distinguished within the territory, characterized by both, specific geological compositions and specific hydrogeologic properties.

2. Diverse aquifer systems

In the northern province Vojvodina, the Neogene and Quaternary sediments are up to 4500 m thick, but major subartesian and artesian aquifers are of Quaternary age (called “Basic Water-Bearing Complex,” tapped up to depth of 230 m (Kikinda). The hydrodynamic analyses indicate that in this region the rate of water abstraction is more than 1 m3/s higher than the rate of recharge. Previously registered significant drawdown in some areas (up to 0.5 m/year) has been relatively stabilized due to lesser water consumption and economic stagnation. Water quality is generally protected from pollution by thick, overlying impervious sediments, but groundwater in deeper structures is highly loaded with organic matter and ammonia, in addition to commonly present arsenic.

The thickest water-bearing alluvial and terrace sediments (up to 30 m) can be found in the Mačva area (alluvium of the Drina River). Closer to Belgrade, the Sava alluvium is also 20-30 m thick and holds a major water source for the City of Belgrade. The alluvial aquifer of the Danube provides water supply for the cities of Novi Sad, Pančevo and Apatin. The Danube alluvium is 15-30 m thick. Groundwater in these alluvial aquifers is exposed to intensive anthropogenic impacts and pollution threats.

The Central and southern parts of Serbia are not as rich in groundwater, and some areas as Šumadija and Vranjsko Pomoravlje even suffer from groundwater shortage and utilize surface waters from reservoirs for water supply. The most important aquifer in this part of country is alluvium of the Velika Morava. Although the minimal riverflow of that main domicile water course can falls below 30 m3/s during autumn months, many cities located along its banks utilize groundwater from its riverbanks. Main deeper artesian aquifers of Neogene age such as Leskovac and Jagodina-Paraćin are also situated in large Morava basin.

Serbia is the single country across which the two main branches of Alpine orogenic belt, namely Dinarides and Carpathian-Balkanides extend. The most important hydrogeological formation in the Dinaric Mountains of Western Serbia is comprised of extensively karstified Middle and Upper Triassic limestones. Among numerous karstic springs, 11 have a minimum discharge of close to, or more than 1000 L/s. The Eastern Serbia is characterized by highly karstified Upper Jurassic and Lower Cretaceous limestones of the Carpathian-Balkan Arch. This region features a large number of karstic springs, 16 of which have a minimum yield of more than 100 L/s. In both of these structures alluvial and lacustrine intergranular aquifers are less significant and their abstraction potential is rather limited.

3. Large groundwater reserves but insufficient groundwater monitoring

The total naturally replenished groundwater reserves is estimated on 67 m3/s. The abstracted amount of water for potable water supply is three time lesser, around 23 m3/s and has not considerably changed during last twenty years. The groundwater sources contribute with some 17 m3/s. More than half of this extraction rate is from alluvial aquifers exploited along large rivers, such as the Danube, the Sava, and the lower courses of the Drina and Velika Morava. These waters are generally abstracted by the bank filtration method. Belgrade residents consume water which originates from thick alluvial deposits of the Sava River (near its confluence with the Danube) or treated river water. The groundwater is tapped by numerous conventional drilled wells and 99 collector wells (shafts with horizontal drains). The current rate of water abstraction from this source is 3.5-4.5 m3/s, although the potential is considerably higher. The second largest source of alluvial groundwater is supplying Novi Sad from Danube alluvium (1.5 m3/s).

The second largest and exploited aquifer system is karstic. The mean specific karst groundwater flow is 5.6 L/s/km2 for Carpathian-Balkanides karst, and 5.5 – 17.0 L/s/km2 for certain regional aquifers in Serbian Dinarides. Karst groundwater potential is 12.6 m3/s and 14.6 m3/s in Carpatho-Balkanides and Dinarides, respectively. However, an average extraction rate from all karst aquifers is just around 15% of the reserves. This is because tapped karst springs are generally characterized by high discharge fluctuations and significantly lower spring yields during dry periods, which is a problem for the most of waterworks. Although highly vulnerable to pollution, quality of karst waters is good to excellent, because the catchment areas are usually sparsely populated.

Groundwater monitoring is far from satisfactory. The Serbian Environmental Protection Agency is in charge of systematic monitoring of groundwater quality in the country, while monitoring the quantity of groundwater falls within the competence of the Republic Hydrometeorological Service of Serbia. However, only about 20% of delineated groundwater bodies (GB, classified in accordance with EU Water Framework Directive) are under systematic observation. There is a noticeable disproportion within the spatial distribution of the observation network in the monitoring of intergranular aquifers on the one side, and in karst aquifers and artesian aquifers in sedimentary basins of Neogene age on the other (which are both scarcely observed).

The analysis showed that, in Serbia, groundwater in general is not under quantitative pressure (only a few monitored GBs were found to be under pressure), while qualitative pressure does exist (around one half of all the monitored GBs are under- or potentially under pressure) and refers to areas with intensive agricultural and extensive mining activity.

4. Considerable potential for artificial recharge and aquifer control projects

Artificial recharge is used rather modestly, a total of some 1.0 m3/s out of almost 40 m3/s, which is an assessed total potential of alluviums. The artificially-recharged “Mediana” water source in the City of Niš is the focal point of this city’s water supply, especially during lean water periods when karst springs reduce their discharges. The system extends over 230 ha and consists of nine infiltration ponds and 14 extraction wells. The system ensures some 0.6 m3/s to the municipal water utility, which together with other karst springs serves some 250,000 inhabitants.

Hydrogeological surveys and feasibility studies undertaken during the last two decades made possible to identify favourable conditions for artificial control of karst aquifers in numerous locations. Based on these results, several successful systems were constructed mostly in Eastern Serbia (Bor, Niš, Ćuprija, Knjaževac). The largest regulation system is constructed for the mining and industrial centre of Bor. After extensive and complex hydrogeological research in 1990s, four exploitation wells were drilled in vicinity of natural Mrljiš spring. Their exploitation capacity of 0.24 m3/s as compared to the minimal springflow, has increased almost four-fold. System is operational since 2002, including the monitoring system on nearby Crni Timok River in order to ensure ecological natural flow for dependent eco systems downstream.

5. Good prospect for developing geothermal projects

Within the territory of Serbia there are 160 natural springs of thermal water with temperature above 15 °C. The thermal springs with the highest temperature are in Vranjska banja spa (96 °C), Jošanička banja spa (78 °C), Sijarinska banja Spa (72 °C) that all belong to the geo-structure of Serbian-Macedonian massif in central Serbia (granitoides and volcanic rocks as main reservoirs).

The yield of 62 artificial geothermal wells in the province of Vojvodina is about 0.55 m3/s and their heat capacity is about 50 MW, while in the other parts of Serbia at 48 wells it is 108 MW, making the total of 158 MW.

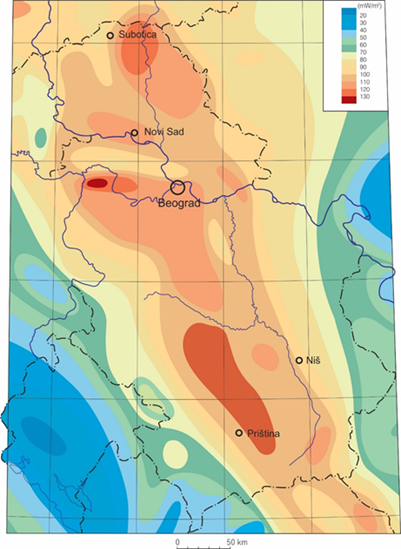

Values of the terrestrial heat flow density under most of Serbia are higher than the average for continental Europe. The highest values (>100 mW/m2) are in the Pannonian basin (N Serbia), Serbian-Macedonian massif (central part) and in Mačva (NW Serbia). Thickness of lithosphere calculated via geothermal model is the smallest in the areas of the most recent (the youngest) tectonic activity, such is the Pannonian basin with its adjacent areas, and in the zone of Neogene magmatic activations.